Utility

Utility

I am very pleased to have been invited to write for the Talking Antiques blog.

This piece is about a small occasional table 29 inches long, 14 inches wide and 15 inches tall. It has a quite thinly-cut mahogany top, a walnut frame and removable legs in a hardwood which is probably birch. It is plain and simple and cheap-looking and featureless and, frankly, quite boring.

This piece is about a small occasional table 29 inches long, 14 inches wide and 15 inches tall. It has a quite thinly-cut mahogany top, a walnut frame and removable legs in a hardwood which is probably birch. It is plain and simple and cheap-looking and featureless and, frankly, quite boring.

The table lives in my attic and only comes out on very rare occasions when I need an additional low table for use in the living room. I bought it a few years ago in a fund-raising auction held at a Church of Scotland parish church near my house. My winning bid was £8. As I was collecting it afterwards a very old lady approached me and said: “I wanted that table. It would look nice in my sitting room. Can I buy it from you for £8?” I refused quite sharply, and she turned away, clearly disappointed at my churlishness. I felt that I’d been slightly rude. After all, it was only a dull dreary coffee table, and her need was almost certainly much greater than mine. I already possess as many other coffee tables as I could possibly require, all of them much more suited to my personal tastes than this specimen.

So why would this frankly rather cheap and unappealing object cause me to be brusque with an inoffensive old lady? Here’s why: because before placing my winning bid I had noted the markings on the underside. It’s not just any old table. It’s a table with stories to tell.

Story Number One is about the maker’s label, a strip of printed plastic bearing the name David Joel. To anyone who knows anything about British 20th century furniture design, that’s a classy name – the husband of the more famous designer Betty Joel (1896-1985). For a while in the 1930s, Betty Joel was the most celebrated and fashionable interior designer in the UK, sometimes referred to as the Clarice Cliff of furniture design. With her husband David she set up the Token Furniture works which met with great success until the marriage broke up and she withdrew from the furniture business altogether. David renamed the firm David Joel Ltd and carried on by himself. This happened in 1939 – note the date.

If you look at online images of Betty Joel’s furniture (like the ones here), you’ll see superb handmade craftsman quality, influences from the later Arts and Crafts Movement as interpreted by the Cotswold school of furniture makers, a dash of restrained Art Deco, a touch of The Jazz Age, and a slight nod to early Modernism. By contrast, if you look at my little table, you’ll see Scandi-influenced minimalism, skimping and haphazard use of materials, signs of  mass-production (despite the “hand-made” claim on the label), and embryonic flat-pack construction. Between the time when Betty left the firm in 1939 and the time when my table was made around a dozen years later, something momentous happened. Here’s a clue: the Second World War.

mass-production (despite the “hand-made” claim on the label), and embryonic flat-pack construction. Between the time when Betty left the firm in 1939 and the time when my table was made around a dozen years later, something momentous happened. Here’s a clue: the Second World War.

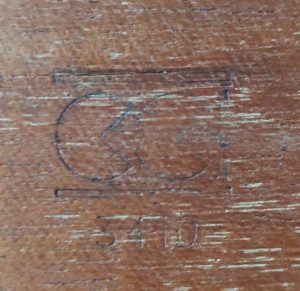

On the underside, above the plastic maker’s label, there’s a stamped logo comprising two circles, each with a small segment cut out. It’s the Utility Mark, and is the table’s Story Number Two. People born in Britain during the War and in the first few years after will be familiar with this logo on products of many kinds. As a baby, you might have been wrapped in a Utility blanket; as a school- child you might have worn a Utility shirt or dress; the mark might have appeared on your furniture and on your kitchen pots and pans. Born in 1948, brought up in London, and interested in labels from an early age, I remember it well. I probably shouldn’t admit this, but I believe we still have a Utility bedsheet in our linen cupboard.

child you might have worn a Utility shirt or dress; the mark might have appeared on your furniture and on your kitchen pots and pans. Born in 1948, brought up in London, and interested in labels from an early age, I remember it well. I probably shouldn’t admit this, but I believe we still have a Utility bedsheet in our linen cupboard.

You can get useful information about the Utility scheme from Google and other online sources. It was a Government scheme brought in during 1941, when all of Britain’s resources were focussed on the War effort, and for every aspect of domestic life, strictest austerity was the watchword. New furniture was only to be manufactured for sale to newlyweds and to those who had lost their possessions in bombing raids, and the items permitted to be made had to conform to very strict regulations and a restricted range of standard designs. Utility furniture was plain and unpopular, but must have been robust because you still see quite a bit of it about in second-hand furniture shops and low-end salerooms.

After the end of the war in 1945, the Utility scheme (together with food rationing and other elements of the austerity regime) was continued through the period of reconstruction, until it was finally abandoned in 1952 – thus providing the latest possible date for my little table to have been made.

If you look at the approved ranges and designs of wartime Utility furniture, you won’t see anything like my coffee table. It’s all very plain and 1940s-looking, again with distant echoes of the Cotswold school, but with no hint of Scandinavian modernism. But in 1948, towards the end of the Utility scheme, the Government design restrictions were relaxed, and registered firms were permitted to introduce their own ranges. So 1948 is the earliest possible date for my table.

David Joel was clearly a furniture maker who took advantage of the relaxation of the Utility regime to produce modernist designs, but during this time makers had to contend with severe materials and labour shortages, with most timber supplies and skilled workers being used for post-war house-building. Hence, perhaps, the rather timid design, sloppy manufacturing and odd combination of hardwoods in my coffee table.

It’s possible to argue that the making of a modern-looking table under Utility regulations is emblematic of a major shift in the prevailing fashionable furniture taste in Britain from the rather stuffy, blocky, arts-and-crafts / art deco, heavyweight oak and walnut pieces inspired by Betty Joel, to the Danish-influenced, lightweight, minimalist teak and rosewood furniture which we now think of as “mid-century modern”. If this is true, then the four-year window between 1948 and 1952 seems like a very short time for a whole new design sensibility to take hold.

But it happened (Story Number Three coming up), largely due to the overwhelming influence of one major event – the Festival of Britain, held on the South Bank of the River Thames in London in 1951.

Much has been written about the influence of the Festival of Britain on British design, and I’m not going to rehearse it all here. Suffice to say that the Government-sponsored Festival, and the artists, craftspeople, organisers, agencies and businesses behind it, were instrumental in sweeping away the dullness and austerity of the War and post-war years, and bringing in a new colourful, modernist, populist aesthetic which has set the tone for much British (and world) design ever since.

The last sentence is a huge generalisation, and people who know much more than me about design (which wouldn’t be difficult) may take different views. But if it wasn’t for the design revolution which took place around the Festival of Britain, I think it very unlikely that my small David Joel coffee table would look anything like it does.

Small table, big stories.

About me

I’m Roger Stewart, a long-time collector and occasional dealer in antiques, artworks and other lovely things. I make most of my finds in local auctions and second hand shops near my home in Edinburgh, the beautiful capital city of Scotland. I like to write about objects that I collect and (sometimes) sell, and you can find stories about some very remarkable items on my blog at www.random-treasure.com and in my book Random Treasure – Antiques, Auctions and Alchemy, available from online booksellers including Amazon at tinyurl.com/y7j7lsys.

I’m Roger Stewart, a long-time collector and occasional dealer in antiques, artworks and other lovely things. I make most of my finds in local auctions and second hand shops near my home in Edinburgh, the beautiful capital city of Scotland. I like to write about objects that I collect and (sometimes) sell, and you can find stories about some very remarkable items on my blog at www.random-treasure.com and in my book Random Treasure – Antiques, Auctions and Alchemy, available from online booksellers including Amazon at tinyurl.com/y7j7lsys.